While New York, New Jersey and Connecticut have not adopted legislation governing green building for homes, some municipalities are moving ahead. Starting April 1, three towns on Long Island are requiring new homes to meet a specific level of green building standards.

“The rhetoric is way out in front of the reality,” said Stephen R. Kellert, professor of social ecology at the Yale School of Forestry and Environmental Studies and a partner in Environmental Capital Partners, a private equity company that invests in environmental industries. “The products, availability and alternatives are increasing very, very quickly, and there’s a gap between that and the knowledge to take advantage of that.”

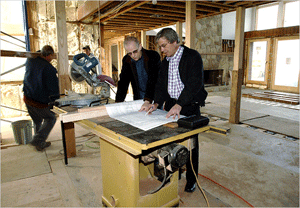

Photo

In Westchester, Stephen Tilly, left, checks plans with Michael DiSisto at the Dobbs Ferry house where foam insulation and floor heating are being installed. Susan Farley for The New York Times

Mr. Kellert, Mr. Suter, other experts and homeowners who have navigated the process suggest seeking a professional to sort through options and steer clear of greenwashing — a derisive term used to describe products and procedures that are barely green. More important, they unfailingly counsel homeowners to focus on the basics. This means recognizing that the greening of a home is a way to use less energy. While sustainable, and usually expensive, accouterments like wood certified by the Forest Stewardship Council, recycled glass countertops and even some energy systems like geothermal ones may be legitimately sustainable, they are not the real paybacks.

“Energy consumption — that’s the big kahuna,” Mr. Suter said. His mantra, and that of just about every other professional involved with building green, is to “get your loads down” first — that is, cut the waste in your energy consumption. Then decide what you really need. “Does a couple with no kids really need a 4,000-square-foot house?” he asked. Then, in industry parlance, make the envelope of the house as tight as you can — essentially sealing it — with proper ventilation to combat mold and other health concerns.

“It was a big learning curve,” said Curt Johnson of his homebuilding project. As senior attorney for the Connecticut Fund for the Environment, Mr. Johnson has spent more time than most on green issues. So when he and his wife, Nancy Dittes, decided to build a 2,000-square-foot home for four on the site of a burned-out house in Branford, Conn., they planned to go as far as they could financially to keep it environmentally sound. But even working with people experienced in green building — their architect is Mr. Suter and their contractor, Jonathan Tuminski of Measure for Measure in Bridgeport — Ms. Dittes said her biggest surprise was “how much time and energy and sleeplessness” were involved.

Their goal was a highly efficient home on a tight budget that is likely to run about $160 a square foot without the cost of the land and with Mr. Johnson and Ms. Dittes doing some of the work themselves. That meant “deals with the devil” like very little lumber certified by the Forest Stewardship Council, which costs 30 percent more, no top-of-the-line energy-efficient windows and no metal roof.

Mr. Johnson and Ms. Dittes chose structural insulated panels — relatively new preinsulated sheets — instead of expensive sprayed-foam insulation like Icynene or blown-in recycled cellulose, which are among several green insulations available. They also took advantage of Connecticut’s generous rebate and loan program, which helped pay for solar panels on the south-facing roof. The house also has several passive solar design elements, which use roof angles and window placement to help with the heating and cooling. The exterior shingles are a concrete and wood fiber aggregate designed to last 50 years.

There is radiant floor heating, and the toilets use rainwater stored in a cistern. The floors, doors and wall paneling are reclaimed from vintage homes that were torn down elsewhere in the state. Instead of copper pipes, water will travel through Pex piping, less expensive flexible polyethylene tubes that are petroleum-based, but still may be greener than copper pipe.

“It is a compromise,” said Mr. Johnson, who said he worried a little about the health aspects of Pex. “I couldn’t get a good read on that, to tell you the truth. I sort of got exhausted in asking a bunch of people.”

Photo

Mr. Tuminski, who like other green contractors has had to train subcontractors in green techniques, said sorting through products and then finding them was so daunting that he and his partner, Erin Buckley, finally opened a store, the Center for Green Building in Bridgeport, to sell green materials they had tested and were satisfied with, like paints that emit little or no gas from the volatile organic compounds (commonly referred to as VOCs) typically present in standard paint. “A lot of the contractors take a little convincing to use these new products,” Ms. Buckley said. “We have people come in here all the time and they’ve done a bit of research and are just overwhelmed by the options out there. We do a lot of educating here.”

Even though Rey Montalvo is an energy consultant, educating is what he needed when mold and flood forced him to renovate his 1,700-square-foot ranch house in Eatontown, N.J. “It was one heck of a learning experience,” he said.

Mr. Montalvo went all out — voluntarily complying with the independent United States Green Building Council’s Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design standards for new homes and gut renovations, known by its acronym LEED. His home was given a gold LEED rating. With many categories, from energy systems to siting to materials, and a third-party certification, LEED has become the premier standard nationally for green building.

In March, using LEED as a framework, the United States Green Building Council and the American Society of Interior Designers released remodeling guidelines known as Regreen, which do not include certification. The Rutgers Center for Green Building is using Regreen to develop green renovation standards specifically designed for New Jersey that eventually could be adopted by the state.

“What we want to do is anticipate what are the typical renovations a homeowner might make and insert green,” said Jennifer Senick, executive director of the Rutgers center, adding that specifications would address the different weather conditions around the state. She said the center constantly gets calls from people who don’t know where to turn for professional help or how to decide on products.

“Advertising and marketing is what’s confusing to the consumer,” said Robert Wisniewski, senior technical consultant at MaGrann Associates, a green-building consulting firm in Moorestown, N.J., who worked with Mr. Montalvo. “In reality, green is not really about what you can see; it’s about good building science. If you want something to show off, you can show off your energy bills.”

And that is precisely what Mr. Montalvo wants to do. His goal is to cut his energy consumption to 70 percent less than a comparable home, which he is doing by using recycled denim insulation and retrofitting his windows. Part of his goal is health, so he has installed a high efficiency particulate air filtration system and a ventilation system that replaces the air in the house with air from outside every three hours. He has also decided to use green products like bamboo for his floors, even though some argue that bamboo is a classic case of greenwashing. (Though it is a fast-growing wood, it is shipped from China, may not be grown sustainably, and turns out to be softer than thought.)

Photo

Like others, Mr. Montalvo found the construction industry lagging in its knowledge of green techniques. “Every time I hired a contractor to do the job, there would be a level of frustration at first,” he said. “I found myself having to teach them how to do it.”

On Long Island, that issue is being addressed out of necessity. On April 1, a level of green building standards became mandatory in Babylon, Riverhead and Brookhaven, the first Long Island town to mandate Energy Star for new homes. Later this year, an additional 4 of the Island’s 13 towns will also require that new homes be built to Energy Star standards.

Administered by the Environmental Protection Agency, Energy Star is known to most people by its yellow tags, which indicate energy-efficiency levels on appliances. But it also has a program that encourages voluntary compliance to green homebuilding standards and that typically functions through power companies, like the Long Island Power Authority, or state entities, like the New York State Energy Research and Development Authority. In some cases, tax credits, incentives or rebates are available if a home meets Energy Star standards.

The three towns’ enforcement of these standards was preceded by 18 months of training for dozens of builders and inspectors. Cliff Fetner, president of Jaco Builders in Hauppauge, and a third-generation builder, said the training opened his eyes to better building science, like improving insulation to allow smaller heating and cooling systems.

“Builders as a group, and I’m one of them, we’re a stubborn bunch — change is tough for us,” he said. “We now have to think of things just differently.”

“I can’t say that I’m looking forward to it,” he said of meeting Energy Star standards, “but I will 100 percent honestly say it’s a better product.”

This is something that Bob Gordon, who manages construction at Emmy Homes of Smithtown, already knew. He has built nearly 150 Energy Star homes since Emmy began voluntarily doing so three years ago. It was an uphill battle, not only in training subcontractors, but also in convincing buyers that they should spend several thousand dollars more for energy efficiency rather than focusing on granite countertops and three-car garages.

Photo

But the changing energy landscape has also inspired people like Jodi Lieberman of Dix Hills to turn to Emmy Homes. “We thought because they’re being conscious of the environment then we should give them our business,” she said.

Some argue that Energy Star sets the bar too low. For Neal Lewis, executive director of the Neighborhood Network of Long Island, the nonprofit alternative energy organization that helped push through the Energy Star mandate, his idea was to start small. “If we can get all of Long Island to one home construction standard,” he said, “that will make the case that the state should do it.”

In Westchester County, without the impetus of a regional mandate, green homebuilding is getting a push from the American Institute of Architects’ Westchester/Mid-Hudson Chapter, which has been holding packed educational sessions for its 600 members, many inundated with requests from clients for green design.

“It’s so overwhelming — they don’t have a clue what they can do,” Ray Beeler, chapter vice president, said of homeowners interested in greening. “They are relying on architects to say what the alternatives are.” But many of the architects, he said, have “a knowledge gap.”

“It’s not just the gadgets,” he said. “It’s not just throwing in the geothermal system. It’s more looking at the house as a whole thing.”

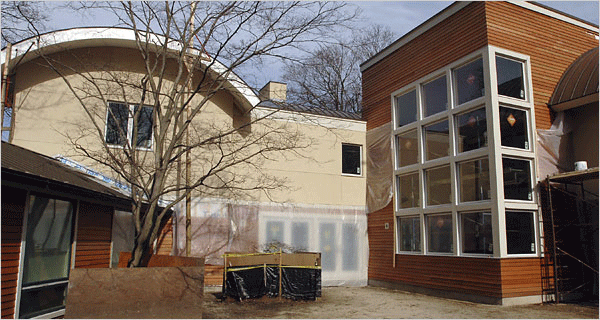

THAT is how Stephen Tilly, an architect in Dobbs Ferry who has been doing sustainable and green design since the late 1970s, approaches his projects. It means, for instance, bringing in the Alaskan yellow cedar that is going on the exterior of one renovation. It’s certified by the Forest Stewardship Council, but still had to be shipped from British Columbia.

“It becomes a gut call and you think, ‘O.K., let’s build durably for the long term and source it F.S.C. and do it on as few materials as we can,’ ” he said. “I’d even consider a stone that has to travel a long distance — because it’s so durable — might be justified.”

Photo

The house Mr. Tilly designed also has a geothermal heating and cooling system costing $27,000 more than a conventional one. Many builders believe a geothermal system is better suited to warmer climates where air-conditioning needs are greater. In the Northeast, they say, the system’s heat pump requires a great deal of electricity during the long heating season.

From Tim Baker’s standpoint, a geothermal system was a worthwhile alternative in transforming his 4,000-square-foot drafty home into a 6,500-square-foot energy-efficient showpiece. The Dobbs Ferry house includes walls lined with top-of-the-line foam insulation, a metal roof ready for solar panels, passive solar design elements and, even though the fireplace (generally not acceptable in strict energy-efficient homes) is huge, it will have tight glass doors and is made from locally quarried stone. The kitchen will have natural quartz and resin countertops, a green alternative to granite. And the walls will be covered with low VOC paint.

“It’s something that my wife and I feel quite strongly about, and because we have the money, quite frankly, we can do it,” Mr. Baker said. “We have 5-year-old twins, and they’re the ones that are really going to feel the impacts of the decisions that are being made.”

For Homeowners, Places to Turn

The United States Green Building Council (usgbc.org), a nonprofit organization, maintains a tremendous amount of information on green building, including its new remodeling guidelines and links to databases on green products and green terminology. The federal Energy Star program (energy-

star.gov) includes a database of Energy Star products and links to building programs and contractors.

CONNECTICUT The residential solar rebate program is handled by the Connecticut Clean Energy Fund (ctcleanenergy.com). Information on the Energy Star program, including homebuilding, is available from the Connecticut Energy Efficiency Fund (ctsavesenergy.org) and through the individual power companies: Connecticut Light and Power (cl-p.com) and United Illuminating (uinet.com).

LONG ISLAND The Long Island Power Authority (lipower.org) offers incentives and rebates for solar energy and incentives through Energy Star.

NEW JERSEY The Rutgers Center for Green Building (greenbuilding-

rutgers.us) has links to many national and state resources. Information on state rebates for solar and wind projects and incentives and loans through Energy Star construction and remediation can be found at njcleanenergy.com.

WESTCHESTER The New York State Energy Research and Development Authority (nyserda.com or getenergysmart.org) offers incentives and loans through Energy Star and incentives and loans for solar energy and geothermal systems.